Is Disney’s Magic Band Secure? This is an interesting paper by Adrian McCabe, a student at George Mason University. He explores the new Disney Magic Bands, My Magic Plus, system at Walt Disney World and what vulnerabilities, if any, there might be. So you are aware, there is no credit card information stored on your Magic Band and to make a purchase you need your band and also your PIN number that you set yourself at Check In. So when comparing your Disney Magic Band to your everyday credit card that you have in your wallet there are several more layers of security in place with the Disney Magic Band. But it’s very interesting to look at the Magic Band system and how it is designed to make hacking it difficult. Here is Adrian’s security assessment for the Disney Magic Bands.

Disney’s MagicBand. A Security Assessment

Adrian McCabe

Department of Computer Science

George Mason University

Fairfax, VA

Abstract—This paper discusses in detail an experimental RFID technology currently being implemented at Walt Disney World. It includes original research pertaining to its architecture, intended usage, security mechanisms, and its basic resistance to common forms of attack.

I. Introduction

Originally founded as a small independent animation studio in 1923, The Walt Disney Company has grown to be one of the largest and most recognized brands in human history. The company is massive, spanning several industries and generating a total gross annual income in the billions of dollars [1]. They are world renowned for their theme parks, attractions, efficient business practices, superb customer service, and of course, a large host of memorable characters.

Yet for The Walt Disney Company, there is one place that is arguably the crown jewel of their corporate empire: Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida.

Walt Disney World is one of the world’s most popular tourist attractions. It contains four separate theme parks, over 20 resort hotels, and a privately owned transportation system using buses, ferry boats, and a mono-rail. It receives millions of visitors annually, and plays a major role in contributing to the company’s multi-billion dollar annual revenue.

Yet despite these impressive statistics, the company promotes a culture that is less focused on returns and most focused on the experiences of the parks’ customers. The company takes each a guest’s visit very seriously, and works as hard as possible to ensure that guests may literally eat, sleep, and live Disney while they spend their leisure time at Walt Disney World.

Undoubtedly, such dedication requires a great bit of supporting effort and engineering to ensure that park operations run smoothly. Often, this means that technology plays a pivotal role in addressing the needs of many at Disney World, and innovative solutions to everyday problems are constantly being explored.

Concordantly, Disney “Imagineers” [7] are constantly working to use technology to improve the experience of the parks’ guests, particularly when it comes to matters of convenience and comfort. In fact, one of their newest creations currently in testing, MagicBand, revolves around this very idea.

II. Introducing the Magic Band

A. Intended Purpose

In addition to simply providing a “magical” atmosphere centered around its parks, Disney World also offers a vast array of services to its guests (some even free of charge). However, these services have each traditionally required a separate form of authentication, and could not be considered integrated by any means. Should a guest wish to take advantage of ALL of the services Disney World has to offer, they would need a separate room key, park admission ticket, photo pass (allows guests to receive “official” Disney copies of pictures) Fastpass tickets (allows guests to skip long lines at attractions), and their individual credit/debit cards.

Undoubtedly, these seemingly disparate system elements are fairly difficult to manage. One of these necessary authentication tokens being lost is a very real possibility, especially when switching rapidly through many different credentials is the only way for users to “correctly” interface with the system. It is for this reason that Disney created the MagicBand.

The intent of the device was to integrate all of the previously separate elements of the system together, thereby enabling guests to experience the benefits of a seamlessly operating system without also requiring them to maintain a plethora of different credentials. In the ideal world of the Disney Imagineers, a guest’s MagicBand would be their all-access pass to the large array of existing services Disney has to offer [8].

B. Technical Specifications

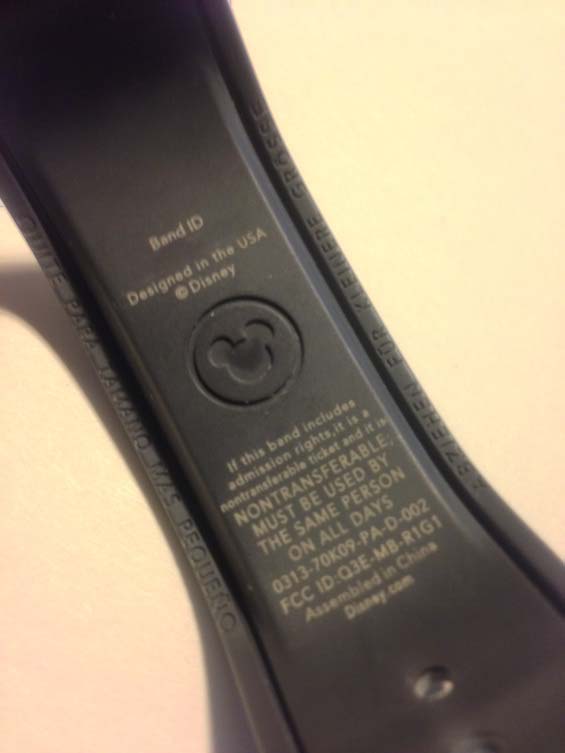

In technical terms, the MagicBand is a lightweight, water-resistant, adjustable bracelet composed of an amalgamation of various polymers (rubber and plastic), designed in USA and assembled in China (Fig 1, Fig 2). It contains a battery-assisted RFID (Radio-frequency identification) tag operating on a 2.4 GHZ band [2]. It has an effective range of 200 meters, and can be used with both long distance and short distance readers.

Fig. 1. The MagicBand

Fig. 2. Inside of MagicBand

III. Band Acquisition and Operation

Currently, the MagicBands are still undergoing pre-release testing [3] and are not widely circulated to the general public. Yet it is still possible for customers who wish to try them on their park excursions to get them, but they must be acquired in one of two ways. A guest may either coordinate with Disney customer service several weeks before they arrive at the parks and have their bands mailed to them, or they may stay at one of Disney’s resorts and purchase them there.

In either instance, there is a strict activation time period associated with the bands before they can be put to use. Additionally, it should also be noted that Disney explicitly states that the bands are non-transferrable, and must be used by the same person throughout the duration of a visit [4].

Given the system’s infrastructure, this is restriction is very easy to understand. Yet perhaps more importantly, this also sets the stage for a plausible attack…

IV. Proposed Attack Process

A widely known vulnerability with the RFID platform is the inherent potential for individual RFID tokens to be cloned. All RFID tokens contain a unique identifier that can be picked up by any receiver operating on the same frequency band within a given distance. By the same token (pun intended), it is also possible to perform a “write” action to an RFID token provided the proper hardware is available.

Bearing this in mind, it would be possible for a malicious user to capture the unique identifier of a MagicBand (from an unsuspecting victim, of course) and create a different 2.4 GHZ RFID token with the same unique identifier. This would therefore compromise the infrastructure of the MagicBand system, and leave certain elements of the system open to further attack.

V. Security Measures

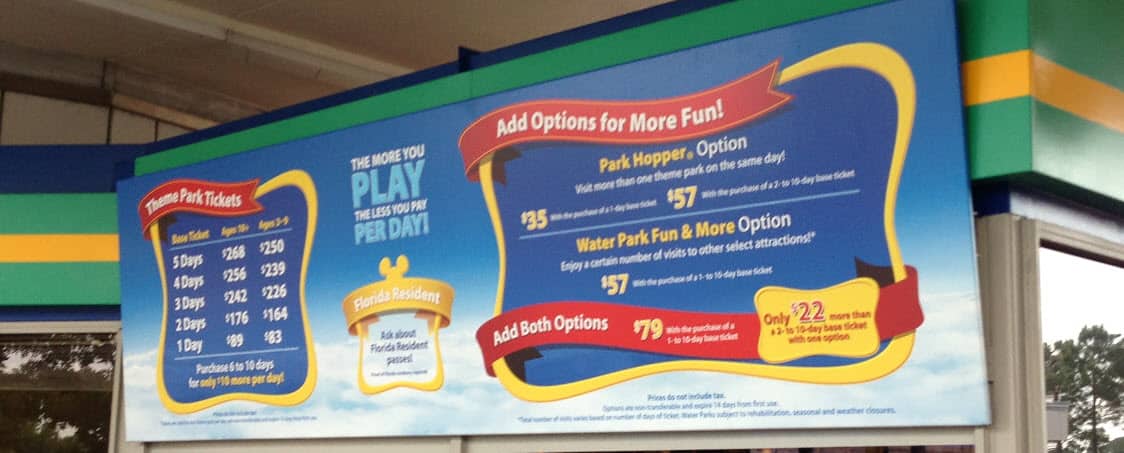

While it is still certainly possible to potentially clone a MagicBand (and thereby gain access to protected resources by impersonating the original band holder), the fact that the band operates on the 2.4 GHZ frequency inherently presents some challenges to any would-be malicious users. Admission to the parks is fairly expensive (Fig. 5) and the cost of the hardware required to conduct such a cloning attack far exceeds the cost of a legitimate day pass. For the attack to even be considered economical, the malicious user must clone many passes over time.

However, for the sake of argument, let the assumption be made that a band has been successfully cloned by a malicious user and he has created a fake. He has used his fancy equipment to lift an RFID code from an innocent victim on the bus ride from his hotel to one of the parks. He then writes the captured code to a band. He puts his equipment back in his bag, and gets out his Disney character autograph book in preparation for a fun-filled day at Disney (for free!). Yet before he can gain entry into the park, he must jump through several hoops in order to partake in the ill-gotten fruits of his labor.

The first obstacle is the presence of physical security (Fig. 3). Disney employs a large amount of park security, and their duties are, among other things, to inspect bags of individuals entering the park. This inspection happens just prior to guests gaining access to the band-reading machines that physically allow visitors to enter the park. It is possible that due to our malicious user’s bag of electronic goodies, he will be stymied at security just long enough for his victims to pass him in line and enter the park before him. If they do, he will be denied entry, as the system will only allow one RFID token with a given unique identifier to be active at a given location at one time.

The second obstacle is the band-reading machine itself (Fig. 4). In order to formally activate a band, it must first be calibrated at a band-reading machine at a park entry gate. The calibration station machine consists of an RFID reader (the big orb with the Mickey on it) and a biometric fingerprint scanner (the arm off to the right). If the malicious user has cloned the band of someone whose band is already activated, his fingerprint will likely not match, and he would be denied entry. However, if he arrives to the scanning station BEFORE the original band-holder has calibrated their band, he may then calibrate HIS band to his fingerprint and proceed into the park uninhibited; it is the legitimate band-holder who would be denied entry.

The third obstacle is another form of multifactor authentication used explicitly for purchases within the parks/resorts themselves. Part of the MagicBand system allows guests to make purchases with the band at specific registers provided they have tied a credit/debit card to their account via an external process. This can be seen as a very big convenience to guests who do not wish to continually use their cards to make purchases while in the parks, or for those who find themselves wishing to buy merchandise when they had not initially anticipated in doing so and do not have their wallet/purse/money clip in their possession. Yet in order to make purchases, a user must first swipe their band against a specially designed reader (Fig. 6) and subsequently enter a matching PIN number.

Even if our malicious user had an RFID token that was a working clone of a legitimate one, it is somewhat unlikely he would be able to successfully guess the matching PIN number within a reasonable number of tries in one sitting before the cashier would begin to get suspicious.

Fig. 3: Disney security

Fig. 4: Entry gate band scanning machine

Fig. 5: The park price board

Fig. 6: A cash register band scanner

VI. Counter-Security Measures

Yet despite these security measures, it is still entirely possible to compromise the MagicBand system provided that a malicious user can obtain a legitimate copy.

While multifactor authentication certainly adds to the security of the system in a significant way, biometric hardware is not flawlessly reliable. Florida is a rather humid place [5] which inevitably affects the performance of sensitive electronic hardware like fingerprint readers.

To address this issue and counteract the likelihood of the system presenting users with false negatives, it would be fair to assume that the fingerprint readers themselves are configured to fail open (ie, when in doubt, allow entry). This gives malicious users the potential benefit of knowing that they merely need to intentionally cause the reader to malfunction to be granted access.

Social engineering could also potentially play a factor in the exploitation of the MagicBand system by using Disney’s own customer-service policy against itself. Suppose our malicious user is successfully stopped dead in his tracks at the gate. He has been beaten to the entry gate by his victims and has lost the calibration race; there is no hope the machine will accept his cloned band. Yet he scans it anyway, and is

denied access immediately. He knows he will not gain entry, but he continues to scan it. The employees at the gate attempt to help him, scanning his band for him, fiddling with the machine, etc, all to no avail. Yet a large line is beginning to form behind him. Technically at this point the gate employees

are supposed to follow a procedure for addressing this issue, but our malicious user doesn’t look like the typical villain, and as Disney employees they must strive to honor their commitment to deliver unforgettable moments (as outlined in their policy [6] ) to their guests. In light of this, they allow him to enter the park despite his seemingly malfunctioning MagicBand. In their eyes, they have provided him with excellent customer service by alleviating a temporary source of frustration, when, in actuality, they have allowed the park admission system to be compromised.

Then there is the matter of the PIN number required to make purchases with the MagicBand. Provided all stages of the attack have worked perfectly (cloned band, successful band calibration, park entry), it is highly unlikely the malicious user will know the PIN number of the band he has cloned. Yet the fact of the matter is that a PIN is still a PIN, and it has been demonstrated time and time again that users will find ingenious ways to make a secure system inherently insecure.

It is common knowledge that some of the most popular PIN numbers include 12345, 54321, and repeating digits such as 12121. Therefore, it may be possible for our malicious user to guess the PIN by attempting to buy something trivial (say, a piece of candy) with his cloned band, entering a common PIN as a guess, and seeing if it works. If it does not, he simply apologizes, pays with cash, and attempts to repeat the process somewhere else with the next most common pin. If he succeeds, he may now buy bigger and more expensive items without fear of getting the PIN wrong during check out and being stuck with trying to appear “normal” by buying the item outright. This iterative process will likely take a moderate number of tries, but it has a somewhat high probability of success if our malicious user sticks with it and continues to work at guessing the PIN.

VII. Conclusion

Despite the inherent arms-race between malicious users and system security mechanisms, overall the MagicBand system seems to hold up under scrutiny and is fairly well designed. The high cost of the hardware required to compromise the system via an RFID cloning attack combined with the multifactor authentication process provides sufficient layers of systematic defenses; even the most judicious adversaries may still fail to successfully thwart system security.

Overall, the MagicBand is a solid piece of technology that will greatly improve the experience of the guests at Walt Disney World. Disney’s Imagineers have effectively consolidated systems that were previously separate, and have provided a way for guests to utilize them in a simple, effective, and secure manner.

Acknowledgments

To my girlfriend, Gracie, who was the inspiration behind this project.

References

[1] “Annual Financials of The Walt Disney Company.” Market Watch. The Wall Street Journal. Web. 28 Nov 2013. <http://www.marketwatch.com/investing/stock/dis/financials>

[2] “OET Exhibits List.” Federal Communications Commission. Federal Communications Commission. Web. 28 Nov 2013. <https://apps.fcc.gov/oetcf/eas/reports/ViewExhibitReport.cfm?mode=Exhibits&RequestTimeout=500&calledFromFrame=N&application_id=427834&fcc_id >.

[3] “MagicBand Eligibility.” Walt Disney World Resort. The Walt Disney Company. Web. 28 Nov 2013. <https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/faq/bands-cards/program-eligibility/>.

[4] “Transferring Magic Bands.” Walt Disney World Resort. The Walt Disney Company. Web. 28 Nov 2013. <https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/faq/bands-cards/transferring-to-friend/ >.

[5] “Annual Average Humidity Levels in Florida.” Current Results. Current Results. Web. 29 Nov 2013. <http://www.currentresults.com/Weather/Florida/humidity-annual.php>.

[6] Manderfield, Katie. “How Disney Creates Magic Moments and Generations of Happy Customers.” The Credits. Motion Picture Association of America, n. d. Web. 29 Nov. 2013. <http://www.thecredits.org/2013/04/flutterfetti-and-impromptu-parades-how-disney-creates-magic-moments-and-generations-of-happy-customers/>.

[7] “Walt Disney Imagineering.” Disney Careers. The Walt Disney Company. Web. 29 Nov 2013. <http://wdi.disneycareers.com/en/default/>

[8] “Magic Bands and Admission Cards.” Walt Disney World Resort. The Walt Disney Company. Web. 28 Nov 2013. <https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/plan/my-disney-experience/bands-cards/ >.

PINs are only 4-digits, but guests may NOT enter set of sequential digits. This eliminates options like 1234, 5678, etc. This makes guessing the PIN a little harder. I imagine that a PIN such as 1111 might be allowed since it’s not sequential. I also imagine that it would be less likely since the restriction on sequential digits has the effect of making the person selecting the PIN slightly more security conscious.

Forget about the theme parks. Think about a cloned wristband giving access to a room inside Disney property. With able observation and minimal disguising, it is possible to reach for valuables inside the room. Then, again, there’s a locker but possibilities are o

Endless.

After a trip to Disney world myself these attacks seems highly unlikely do to several security measures.

One of them is that the 2.4Ghz transmitter does not have the same ID as the passive 13.56Mhz NFC card which is used to authenticate the user with TicketValidators Kiosk etc. The only thing the 2.4Ghz transmitter does is transmitting its id to receivers so disney can see your movement throughout the park it is also used to link attraction pictures to that user so if you manage to get the 2.4Ghz id of a band you would be able to add some wierd pictures to their photo account but thats about it. And cloning the NFC part of the card is highly unlikely as it is a mifare desfire card and the only thing the id is used for is to calculate the encryption / decryption key to other pages of the card which holds another random id used for authentication to readers this means that just copying the id won’t get you anywhere without knowing the algorithm and the shared secret between the readers and unless you work for Disney or the partner which provide this equipment you can’t do much